The Big, Beautiful Bill: David Bahnsen’s Economic Verdict

My Wealth Advisor’s Take on the One Beautiful Bill Act’s Promises and Perils

⏱️ 6-7 min read

My friend David Bahnsen, a wealth advisor (my wealth advisor, actually) with a razor-sharp mind for economic policy, recently unpacked the One Big Beautiful Act (OBBA) in his Dividend Cafe newsletter. His ability to cut through all of the spin and noise and focus on what drives growth makes his insights essential. As someone who values policies that fuel prosperity, I am eager to share David’s take on this sprawling legislation, summarizing its economic wins, flaws, and implications. Before diving into the details, I should note that David approaches economic analysis with an unwavering commitment to calling balls and strikes as he sees them, focusing on economic truth rather than political allegiance. This perspective challenges both sides to think harder about growth and stability, which is exactly why his analysis proves so valuable. (Translation, if you’re looking for an analysis that says everything in the new law is amazing, or everything in the law sucks, you won’t find it here,). Below, I distill his analysis, though I would encourage you to take it all in using the links or embedded video below.

Tax Cuts Extended, Debt Ceiling Raised

David notes that the OBBA extends the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, preserving lower income tax rates, doubled standard deductions, and enhanced child tax credits set to expire in 2025. Without this, 62% of taxpayers faced hikes. A temporary boost—$1,000 for singles, $2,000 for married couples—targets those earning under $100,000. Yet, David warns of the $5 trillion debt ceiling increase to fund it, a move he sees as delaying tough fiscal choices while betting on short-term relief.

Campaign Promises with Limited Impact

The bill delivers on campaign pledges like “no tax on tips” (up to a $25,000 deduction) and “no tax on overtime” (up to $12,500), both expiring in 2028, plus auto loan interest deductions. David is critical, arguing these lack growth potential. They favor certain workers—servers over truck drivers, for example—creating unfairness and risking tax code gaming. He views these as political maneuvers, not supply-side policies that broadly boost the economy.

Business Provisions That Drive Growth

David is more enthusiastic about the bill’s business tax changes. Permanent 100% expensing for capital equipment, R&D, and factory construction, plus enhanced corporate interest deductions, could pump $100 billion into businesses in 2025 and $130 billion in 2026. Making the 20% small business tax break permanent supports LLCs and partnerships. These measures, David argues, are true pro-growth policies, spurring investment and innovation essential for economic strength.

Spending Restraint Falls Short

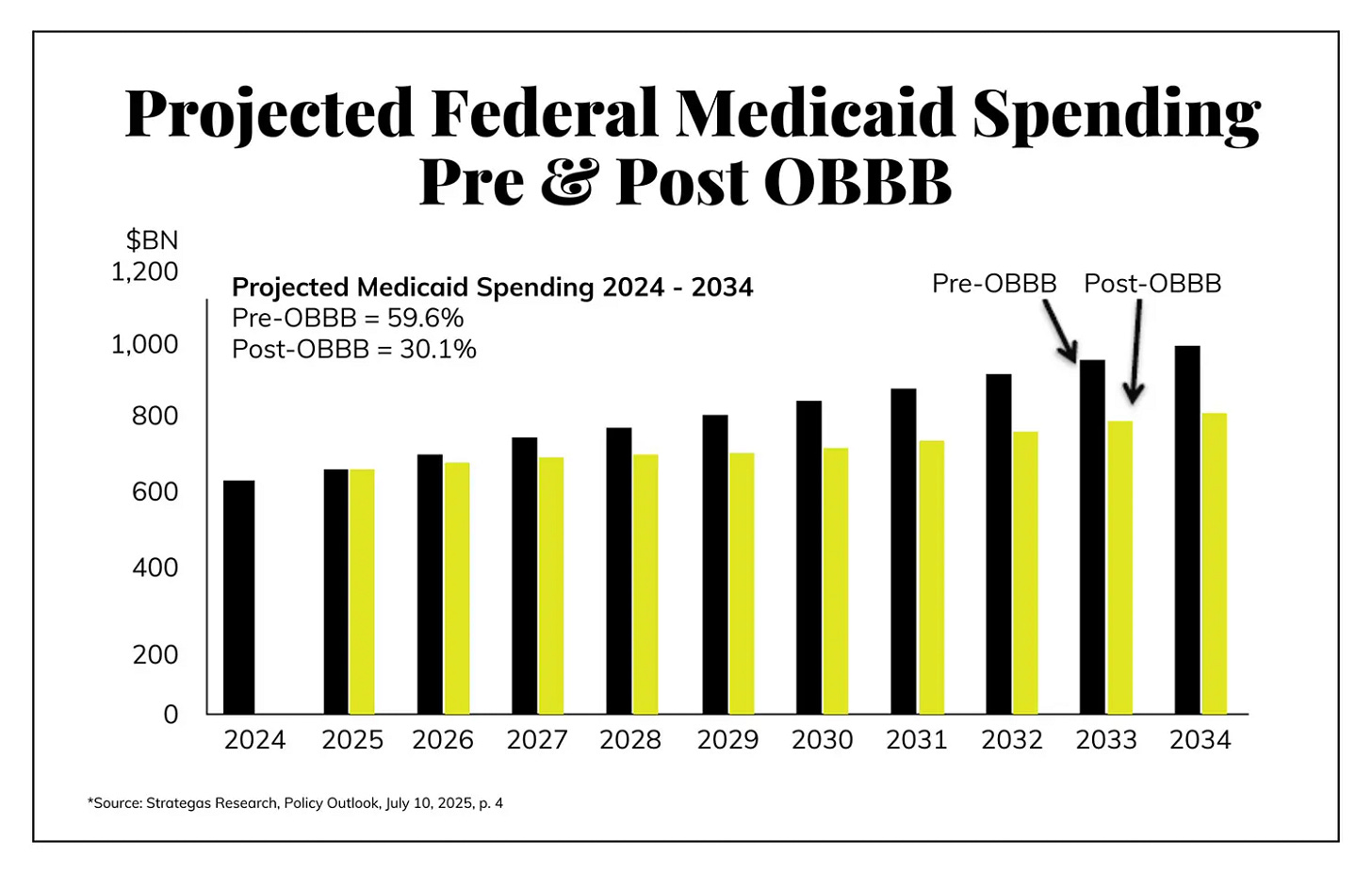

The OBBA trims $1.5 trillion over ten years from planned increases in Medicaid, student loans, and renewable energy. David clarifies these are not cuts but slowed growth. Medicaid changes, delayed until 2028, focus on removing ineligible enrollees and adding work requirements. With federal spending at $6.8 trillion annually, the $150 billion yearly savings is modest, David notes, insufficient to tackle the broader fiscal challenge. I flat out “borrowed” this chart from David’s Dividend Cafe post to give you a visual on how the “cuts” to Medicaid spending over the next decade or so are actually reductions in planned increases in Medicaid spending. Any reductions are more than welcome, but context is alway important.

The Debt Crisis Ignored

David’s sharpest critique is the bill’s failure to address America’s debt trajectory. He estimates it adds at least $3 trillion to the national debt, likely more. Federal spending, at 23.7% of GDP since 2020, exceeds the historical 18-20% norm, with deficits at 5-7% of GDP. David insists a 3% target is critical. He doubts future governments will act if a unified Republican Congress did not.

Political Compromises Miss the Mark

David sees the SALT deduction—capped and phased out above $500,000—as a clumsy compromise for high-tax state Republicans, perpetuating tax code inequity. The tip and overtime deductions feel like vote-buying to him, not principled policy. He laments the bill’s failure to curb post-2020 spending excesses, a missed chance for fiscal discipline.

A Measured Assessment

David credits the bill for averting a $2 trillion tax hike that risked recession. Its business provisions fuel growth. Yet, the debt increase and selective tax breaks threaten stability. Growth, David argues, demands fiscal discipline.

You can read David’s full take here (with a lot of useful charts):

Below is information to listen or watch.

Jon as you may remember my dissertation (from USC's Price School) was on the income tax. And for the most part I agree with Banshen's analysis. Had I been the decision maker I would have eliminated the SALT limit entirely - forcing those of us from high tax states to quit being subsidized by middle and lower income tax payers in lower tax states. That might put a fire under the California legislature to change their view on the efficacy of extreme tax rates. The data on how much those provisions actually raise suggested that the Legislature is always overly optimistic. I have not looked at the distributional analysis from the FTB on who actually pays the California personal income tax - but I do know that when federal rates have been reduced that the share of income taxes paid by the highest earners actually rises. I have done some crude analysis on the deficit effects of the bill and I think the estimate of $3 trillion in cost is a bit off. But the National Debt numbers are very scary and the Congress should begin to do something about it. For the last couple of years interest in the national debt as a share of the budget has been rising. I think the business tax provisions have the possibility of adding a bit more growth than the CBO and JCT projected. Since the 2017 projections were done, the Washington estimates underestimated the revenue/growth effects by about $1.5 trillion. Finally there are some other dynamic effects that I think some have not considered. For example, if we cannot use migrants for agriculture or in other areas where they are critical to the California economy - we might well have diminished output.